The History and Life of the Warwickshire Village

of Lillington

Lillington, once an independent rural settlement and now a suburb of Leamington Spa, boasts a

rich history spanning over a millennium. Originally a Saxon settlement that evolved through

medieval abbey ownership to become a thriving agricultural community, Lillington’s character

has been shaped by changing land ownership, industrial development, and eventually suburban

expansion. This report traces its evolution from early origins documented in the Domesday Book

through its agricultural heyday, Victorian expansion, and eventual integration with Leamington

Spa, revealing how this ancient settlement has maintained elements of its village identity despite

significant urban development.

Geographic Setting and Early Origins

Lillington sits northeast of Leamington Spa in Warwickshire, England. While now firmly part of the

Royal Leamington Spa civil parish maintains a distinct identity as a historical settlement

and modern residential district. The area features the Campion Hills, which rise to 97m 318 ft

above sea level and offer panoramic views across Leamington Spa.

This elevated terrain has

made Lillington a prominent geographic feature in the landscape, with Eden Court, its fifteen-story tower block, visible for miles around.

Archaeological evidence confirms human activity in the area long before written records began.

Stone Age remains and prehistoric elephant and woolly rhinoceros fossils were discovered in the

The Cubbington Road area attests to the area’s ancient past. Roman artefacts and burials have also

been uncovered in the vicinity of Highland Road and Braemar Road, indicating continued

settlement through different historical periods.

By the time of the Norman Conquest, Lillington was already an established settlement.The

Domesday Book of 1086 records it as having approximately 16 households, suggesting a

population of about 50 people. Following the Norman Conquest, William I granted the land

to the Count of Meulan as a reward for his service at the Battle of Hastings. This marked the

beginning of the documented history of Lillington’s changing ownership and development.

Medieval Period and Religious Influence

The medieval period brought significant changes to Lillington’s ownership and character. In 1121,

the manor of Lillington was given to Kenilworth Abbey, beginning over four centuries of monastic

influence. This ecclesiastical connection profoundly shaped the village’s development and

religious life.

Evidence of Lillington’s pre-Norman religious significance survives in its parish church. St. Mary

Magdalene Church contains Saxon elements, including part of the south wall of the present

chancel and a Saxon doorway dating from approximately 1020, which was reportedly repaired

after Canute’s 1016 raid into Warwickshire. This doorway represents a thousand-year-old

architectural connection to Lillington’s earliest Christian community.

By around 1380, the chapel had developed into a proper parish church with chancel, nave, and

a short south aisle of two bays. Further architectural development continued with the addition

of the west tower around 1480, which still houses a contemporary bell cast around this time and

dedicated to St. Catherine. The bell hangs in the tower today, connecting to Lillington’s medieval past.

The religious landscape of Lillington underwent dramatic change during the Reformation. When

Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries in 1538; Lillington’s long relationship with Kenilworth Abbey

ended. The village’s lands returned to secular ownership, marking a significant

transition in the community’s history.

Post-Reformation Ownership and Development

Following the dissolution of Kenilworth Abbey, Queen Elizabeth I granted the manor of Lillington

to Sir John Puckering of Warwick in 1596.

The Puckering family maintained ownership until

1709, when they sold the estate to Henry Wise, marking the beginning of the Wise family’s

significant influence on Lillington’s development.

Understanding property boundaries became increasingly crucial as land changed hands. In

1711, Henry Wise commissioned James Fish to create “an exact map” of Lillington. This map,

an essential historical document, revealed the medieval three-field system still in operation, with the

land divided into strips to ensure each tenant farmer had an equal share of the good and the poor

land.

The map also documented the pattern of roads, many of which remain recognisable

Today, despite name changes, it showed the cottages and principal farms clustered near the

church and Manor House.

Fish was commissioned to resolve disputes between Lord Brooke and Henry Wise regarding land

ownership, as these disagreements had become “very inconvenient, …and have often occasioned

disputes in ploughing, in mowing their grass, and is a discouragement to husbandry”. These

Disputes were finally settled in 1730 under the Enclosure Act, when the great fields were divided

and assigned to specific farms and landowners

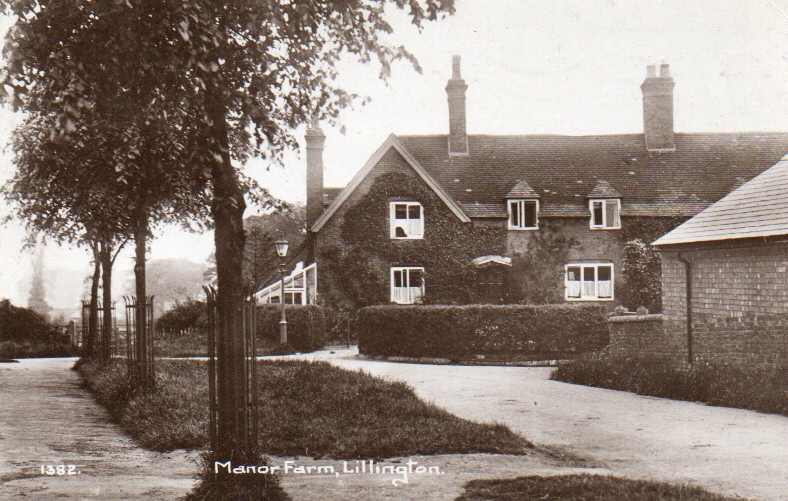

The fields were reorganised and allocated

to the three main farms: Manor Farm (in Lime Avenue), Village Farm (where Tesco’s now stands),

and Grange Farm on Cubbington Road near Pound Lane.

Through the 18th and 19th centuries, the Wise family maintained significant influence in

Lillington. By 1870, H. Wise, Esq., owned the manor and most of the land. The Wise family’s

Connection to Lillington eventually gave way to the Waller family, who sold the last of their

Lillington landholdings in the 1920s.

Victorian Expansion and Industrial Development

The 19th century brought substantial change to Lillington, mainly due to the growth of

neighbouring Leamington Spa as a fashionable spa town. By 1870, Lillington parish covered 1,324

acres with real property valued at £6,460. The population grew from 309 in 1851 to 480 in

In 1861, an increase was attributed to expanded housing accommodations.

This period established several prominent residences, including Lillington House, Blackdown House,

and Elm Bank.

The popularity of Leamington’s spa waters directly impacted Lillington’s development.

Wealthy families built substantial houses along Lillington Avenue, creating employment

opportunities for local people as gardeners and servants. By the end of the 19th century,

increased housing demand led to constructing of terraced houses in Lime Avenue, Manor

and Farm Roads, and along Cubbington Road.

Industrially, Lillington developed several significant enterprises. Brick production became an

important local industry, with evidence of brickmaking dating back to at least 1808.

The 1886 Ordnance Survey map shows several kilns, a chimney, and a light railway on land now covered

by Waller Street, Campion Road, Greville Street, and Villiers Street. The brickworks, owned by

the Wise family and leased to contractors, utilised the area’s clay deposits, with an 1884 lease

permitting clay extraction to a depth of three feet for “bricks, quarry tiles and pipes”.

Other industries included a brewery on Lillington Avenue (now converted to residential use as

“The Maltings”) and several sand and gravel extraction pits near the centre of Lillington.

These industries, along with agriculture, employed the growing population.

Education and Community Development

As Lillington’s population grew, so did the need for educational facilities. In early Victorian

In England, the Reverend John Wise recognised the need for formal education in the village.

The first school building was constructed with a school room on the ground floor and the

schoolmistress’s accommodation on the upper floor. By 1864, the building was extended to

serve multiple purposes: a school during the day and “a reading room for the labouring men of

the village” at other times. This facility became Lillington’s first library, demonstrating the

village’s commitment to education and community development.

The school became increasingly popular, with classes sometimes numbering up to 60 pupils of

different ages and abilities under the instruction of monitors (older children) and pupil teachers

working under the schoolmistress’s direction. Education became free in 1890/91,

marking a significant step in the community’s educational development.

The village’s community infrastructure continued to develop throughout the late 19th and early

20th century. The Imperial Gazetteer of 1870 notes a national school and a

working-men’s reading room.

The parish church of St. Mary Magdalene underwent significant

restoration and enlargement between 1847 and 1884 to accommodate the growing

population.

The McGregor Era and Horse Breeding

The early 20th century saw the rise of another influential family in Lillington’s development,

McGregor’s. Edward McGregor and his sons, Sydney McGregor and Edward Jr., played

instrumental roles in developing the eastern and southern parts of the village from around 1928

through the 1970s.

Sydney McGregor 18891970) established Lillington as a centre for horse breeding through his

stud farm. His most famous horse was April the Fifth, which won the Epsom Derby in

1932. April the Fifth was a British Thoroughbred racehorse bred by McGregor in partnership

with Mr. G.S.L. Whitelaw at the Lillington Stud near Leamington Spa. The horse was foaled on

April 5, which was also McGregor’s birthday.

After Sydney McGregor died in 1970, the stud farm area was developed for housing, with

many new roads being given racing-related names, such as Epsom Road. This development

represented a significant transition from agricultural to residential use, reflecting broader

changes in Lillington’s character.

Twentieth Century Expansion and Integration with Leamington Spa

Lillington’s transformation accelerated in the 20th century. In 1890, the village was incorporated

into the borough of Leamington, marking the end of its administrative independence. By 1901,

The parish had a population of 1,241. On April 1, 1902, the parish was officially abolished to

form “Leamington”.

Buildings continued after World War I, with the Holt development being constructed to rehouse families

relocated from Leamington’s worst slums. The most extensive building program followed

World War II, when the McGregor brothers sold their land for extensive building north and south

of Cubbington Road. The street names reflect their interests: Scottish names from Lime Avenue to

Telford Avenue and racecourse names honour the area’s history as a stud farm.

The new centre of Lillington formed around Crown Way, which opened in the early 1950s. This the

area was predominantly built as a council house estate and includes three tower blocks, with the

Fifteen-story Eden Court is the most prominent. The last of the original cottages in

Cubbington Road was demolished in the 1970s, symbolising the completion of Lillington’s

transformation from village to suburb.

Modern Lillington retains two distinct areas: the newer Crown Way centre with its shops and

amenities, and the older area containing the former village core with the parish church, manor

house, Victorian terraced houses, and post-1930 housing estates. The community continues

to evolve, with former facilities repurposed: the police station became a dentist’s office, the

Walnut Tree public house became a Tesco supermarket, and the original library became a

nursery school.

The Mystery of J.F. Rollason: Exploring a Lillington Jockey’s Death in 1907

Historical Background and Identity

Lillington jockey named JF Rollason who died in a According to historical records, a man named John Francis Rollason (1887-1907), described as a “well-known Leamington jockey,” was buried in Lillington following his death at age 20.

Historical documentation indicates that Mr. Rollason’s funeral occurred on February 27th, 1907, at St Mary’s Church in Lillington. Records note a “large gathering of people” in attendance. This suggests he was of some local significance, aligning with his description as a “well-known” jockey.

Cause of Death: Maritime Incident

The information I have found indicates that Mr John Francis Rollason drowned in the sinking of the ship “Berlin” off the Hook of Holland with his father, Edward Rollason, on their way back from a racing engagement in Holland on February 27th 1907.

The timing of his death and funeral in early 1907 places this tragedy in the Edwardian era, a

period when maritime travel remained the primary means of international transportation.

The Leamington Brick Company:

Its Association

With Lillington and Industrial Infrastructure

The Leamington and Lillington brick works represent a fascinating chapter in local industrial

history, operating from the nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century. This report

examines the connection between the brickworks and Lillington village, the clay and material

extraction sites, and the light railway system that served the industrial operation.

Historical Development and Ownership

The Leamington and Lillington brick works operated from the nineteenth century until the 1950s,

situated off Campion Road in Leamington Spa. Evidence suggests that brick production in the

area dates back to at least 1808, with correspondence between Edward Willes (the original

owner) and his agent referencing small brick kilns on various construction sites. By the late

nineteenth century, the operation had expanded significantly.

The brickworks were initially owned by Edward Willes of Newbold Comyn and covered an

extensive area between Midland Oak Park, Leicester Street, and Lillington Road. The Wise

family later acquired ownership and leased the works to various contractors. An 1884 lease

between George Wise and Mann & Mills specified that clay could be extracted to a depth of

three feet for manufacturing “bricks, quarry tiles and pipes,” with the requirement that topsoil be

replaced afterwards for cultivation.

Ownership changed again when the operation was briefly held by the Leamington & Lillington

The Brickyard Company was purchased in 1891 by Henry Hawkes. By its

closure around 1960, the bricks were fired in a large Hoffmann kiln.

Geographic Extent and Local Significance

The Leamington and Lillington Brickworks were firmly established in the local landscape,

appearing on the Ordnance Survey map of 1886. They were located in what is now the area

of Hazel Close in Leamington Spa, with operations spanning lands that are currently occupied

by the eastern parts of Waller Street, Campion Road, Greville Street, and Villiers Street.

The brick yards in Leicester Street were notably part of the manor of Lillington, establishing a

clear administrative connection between the industrial operation and the village. The 1886

The Ordnance Survey map shows several kilns, a chimney, and, importantly, a light railway system

operating within this area.

The products of the brickworks became integral to local architecture, with their bricks found in

almost all Victorian and Edwardian buildings throughout both Leamington and Lillington. The

operation continued to support the local building industry until its closure around 1960.

Clay Extraction and Material Pits

The Cliffs and Material Extraction

A significant feature of the brickworks operation was an area known as “The Cliffs,” which ran

across the back of the site where Kiln Close is now located. This was characterised by an almost

sheer face of heavy clay with steps (locally called the “Monkey Steps”) cut into the face,

leading to old allotments behind Gresham Avenue.

Beyond its industrial function, this area served a social purpose for the community, becoming a

regular playground for local children on weekends when machinery was inactive. It also provided

a convenient pedestrian route from Campion Hills and Lillington Prefabs down to town.

Sand and Gravel Extraction.

In addition to clay extraction, several pits are slightly north of where Elm Bank Close backs onto

Lillington Close were used for sand and gravel extraction. These materials were in high demand

during the nineteenth-century building booms in Leamington. The local geology proved ideal

for obtaining various building materials, making the area a natural choice for this industry.

The Light Railway System

Transport Infrastructure

One of the most intriguing aspects of the brickworks was its transport system. Evidence

confirms the existence of a small tramway system within the Leamington brickworks. Physical

remains of a railway track have been documented at the end of gardens where Elm Bank Close

backs onto Lillington Close.

The 1886 Ordnance Survey map of Leamington explicitly shows a light railway on land now

covered by residential streets, providing contemporary evidence of this industrial

infrastructure. This light railway would have been typical of industrial operations of the period,

with tracks that could be easily lifted and relocated as needed.

Operation and Evolution

In the 1930s, this small railway was explicitly used to transport clay from the extraction pits to

processing areas where it was crushed into powder. The transportation system evolved, with the railway eventually replaced by a dumper truck by the 1950s as

mechanisation advanced.

The operation of the railway likely varied over its lifetime. Historical evidence suggests that in

similar light railway systems, wagons were either moved by horses or pushed manually by

workers, who would take advantage of natural gradients when possible.

I know that steam engines worked this particular railway that ran between Leamington Brickworks and Lillington Village, I know this because in 1958 I found a full-size Steam engine in a small coppice of trees at the bottom of Lillington Close. Like most boys, I was into trains at that particular time. This steam engine was about 11 feet long. It had three steps up to the cab, which was quite big, enough to get three eleven-year-old boys to jump around and have a great time. Later that year it disappeared I think it was sold for scrap but don’t know any more about it.

There were quite a few Railway lines in the coppice. The steam engine stood on some of these. I recognised these lines because they were the same size as some that had been running down Valley Road when we moved to Lillington in 1952. They came from the direction of the Council rubbish tip, where the Catholic Church in Valley Road now stands. By 1954, the lines had disappeared, and the new playing field for Lillington Junior School was being built.

I used to get beautiful watercress out of the Bins Brook, which ran parallel to the railway line and where Valley Road is now.

Religious Life and Community Identity

Despite changes, religious institutions have remained central to Lillington’s community identity.

St. Mary Magdalene Church continues as the parish church, preserving its ancient heritage while

serving the contemporary community. The Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady in the Valley

Road, consecrated in 1963, features notable stained glass in the ‘Dalle de verre’ style designed

by Dom Charles Norris of Buckfast Abbey. Lillington Free Church on Cubbington Road

represents another significant religious community.

Community identity is also preserved through organisations like the Lillington Local History

Society was founded in 2009 to promote the study of local history and foster a sense of belonging

among residents. The society organises discussions, talks, and visits, encouraging research

into local stories and maintaining connections with neighbouring communities.

Modern Lillington

Today, Lillington serves as a suburban ward of both the Warwick District Council and the Royal

Leamington Spa Town Council. Recent census data shows a relatively stable population:

12,031 in 2001, 11,930 in 2011, and 11,908 in 2021. The area maintains educational facilities,

including Lillington Nursery and Primary School, Telford Infant and Junior Schools, with North

Leamington School serves as the nearest secondary school. A Sure Start Children’s Centre

opened in 2006, adjacent to the community centre and Lillington Library on Mason Avenue.

Notable landmarks include the Midland Oak at the junction of Lillington Avenue and Lillington Road, which marks the supposed centre of England.

The original oak, thought to have dated

from the 16th century, died and was removed in 1967. Its successor was planted in the 1980s

from an acorn collected from the original tree.

The Campion Hills continue to serve practical and recreational purposes, hosting Leamington’s

transmission tower, the Severn Trent water treatment plant, and a BMX track run by Warwick

District Council. These hills offer panoramic views over Leamington Spa and beyond,

connecting modern residents with the landscape that has shaped Lillington’s development for

centuries.