The History of Bishop’s Tachbrook

Bishop’s Tachbrook is a historic Warwickshire village with over a millennium of recorded settlement, evolving from a Saxon episcopal estate through medieval ecclesiastical ownership to a modern rural parish that has recently experienced significant expansion.

Origins and Etymology

The village’s distinctive name reflects its ancient origins and ecclesiastical connections. The second part, “Tachbrook,” derives from Old English meaning “boundary,” referring to the brook that flows north to northeast of the village. This waterway was recorded in 1033 as the boundary between the ancient Saxon dioceses of Worcester and Lichfield. The prefix “Bishop’s” originated from Norman episcopal ownership, distinguishing it from other settlements along the same brook.

Domesday Book and Early Medieval Period

Bishop’s Tachbrook appears in the Domesday Book of 1086, where it is listed in Tremlow Hundred. The entry records that “The Bishop (of Worcester) also holds 7 hides in (Bishop’s) Tachbrook. Land for 12 ploughs. In lordship 2 ploughs; 9 slaves. 11 villagers with a priest and 7 smallholders have 9 ploughs. 2 mills at 12s 8d; meadow 12 acres”. The settlement’s value had increased from £3 before 1066 to £7 by 1086, indicating prosperous development following the Norman Conquest.

Prior to the Conquest, the manor had been held by the diocese of St. Chad at Lichfield. By 1086, it was transferred to the Bishop of Chester, and its rateable value was recorded as 7 hides. The medieval settlement based on the 1886 Ordnance Survey map shows evidence of “thin occupation” with most plots containing trees, suggesting possible settlement shrinkage over time.

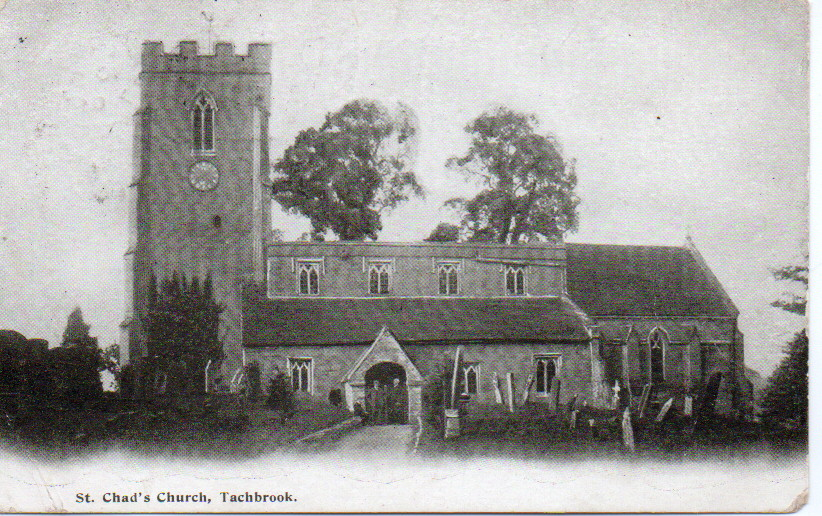

Ecclesiastical Ownership and St. Chad’s Church

The Church of St. Chad, mentioned in the Domesday Book with its priest, became the centerpiece of the village. The current stone church originated in the mid-12th century, with the north aisle added in the 14th century and the south aisle in the 15th century. The church is named after St. Chad, who became the first bishop of Mercia in 669.

The village remained under ecclesiastical ownership until the English Reformation in the 16th century, with one notable exception. Bishop Hugh De Nonant fell from royal favor following a dispute with King Richard I, and the village lands were seized by the crown. However, Bishop’s Tachbrook was restored to the church in 1195.

Post-Reformation Secular Ownership

Following the Reformation in 1529, Parliament sequestered church lands and sold the estate to Thomas Fisher. The property subsequently passed to Edward Ferrars of Baddesley Clinton in 1602, then to the Wagstaffe family and their descendants until 1780. In that year, the lands were sold to the Earls of Warwick, where they remained until the 1950s when the Earl began selling off houses and land.

Tachbrook Mallory and Settlement Consolidation

The parish historically included the hamlet of Tachbrook Mallory, which experienced dramatic depopulation in 1505 due to enclosure of 310 acres for sheep farming. This enclosure forced 60 people to leave, and by Dugdale’s time (mid-17th century), only four houses remained. The deserted medieval settlement has been identified through archaeological evidence, including 13th and 14th century pottery finds. The remains of the medieval Chapel of St. James at Tachbrook Mallory were incorporated into a later farmhouse, with the chapel dating to a 1336 endowment by John Mallory.

Notable Historical Connections

Bishop’s Tachbrook has connections to several prominent historical figures. The poet Walter Savage Landor lived in the village as a child during the 1770s, residing in what is believed to be the Manor House dating back to 1558. His family owned estates in the area, and his mother sold the Tachbrook estate for £20,000 to help finance his purchase of Llanthony Abbey.

Charles Kingsley, the Victorian novelist and author of “The Water Babies,” also had family connections to the village. His widow lived at Tachbrook Mallory, and a memorial window to her was installed in St. Chad’s Church. The eastern window of the church commemorates Elizabeth Kingsley.

20th Century Development and Modern Era

The 20th century brought significant changes to Bishop’s Tachbrook. During World War II, the area had strategic importance, evidenced by the remains of a searchlight battery identified through aerial photography. A war memorial in the village commemorates local residents who served in both World Wars.

The Earl of Warwick’s estate began fragmenting in the 1950s, leading to gradual residential development. Notable architectural additions included Greys Mallory (originally called Greystoke), an Arts and Crafts house built in 1903-1904 by architect Percy Morley Horder. Horder later designed the nearby Mallory Court in 1914.

Contemporary Transformation

The early 21st century has seen unprecedented expansion of Bishop’s Tachbrook parish. According to the 2001 census, the population was 2,514, increasing to 2,558 by 2011. However, major housing developments have dramatically altered the demographic landscape. The parish now includes significant new communities north of the original village, including developments at The Asps, Heathcote, and Oakley Grove.

Recent archaeological work at The Asps revealed extensive prehistoric and Roman settlements predating the medieval village, including Iron Age roundhouses, Roman-period farming settlements, and three cremation burials. This discovery has provided new insights into the area’s long history of continuous occupation.

The village maintains its rural character through conservation efforts, with a Conservation Area designated in 1969 and extended in 2001. Modern amenities include The Leopard public house (parts of which were formerly a morgue for the nearby crematorium), a primary school, The Meadow park with its BMX track, and the Guide Dogs for the Blind Association breeding center.

Today, Bishop’s Tachbrook represents a successful blend of historical preservation and modern development, maintaining its identity as a cohesive community while accommodating significant population growth through carefully planned housing estates that respect the village’s medieval origins and rural setting.